Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the Hip (DDH)

The hip is a “ball-and-socket” joint. In a normal hip, the ball at the upper end of the thighbone (femur) fits firmly into the socket, which is part of the large pelvis bone. In babies and children with developmental dysplasia (dislocation) of the hip (DDH), the hip joint has not formed normally. The ball is loose in the socket and may be easy to dislocate.

Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the Hip (DDH)

Description

In all cases of DDH, the socket (acetabulum) is shallow, meaning that the ball of the thighbone (femur) cannot firmly fit into the socket. Sometimes, the ligaments that help to hold the joint in place are stretched. The degree of hip looseness, or instability, varies among children with DDH.

- Dislocated. In the most severe cases of DDH, the head of the femur is completely out of the socket.

- Dislocatable. In these cases, the head of the femur lies within the acetabulum, but can easily be pushed out of the socket during a physical examination.

- Subluxatable. In mild cases of DDH, the head of the femur is simply loose in the socket. During a physical examination, the bone can be moved within the socket, but it will not dislocate.

In the United States, approximately 1 to 2 babies per 1,000 are born with DDH. Pediatricians screen for DDH at a newborn’s first examination and at every well-baby checkup thereafter.

Cause

DDH tends to run in families. It can be present in either hip and in any individual. It usually affects the left hip and is predominant in:

- Girls

- Firstborn children

- Babies born in the breech position (especially with feet up by the shoulders). The American Academy of Pediatrics now recommends ultrasound DDH screening of all female breech babies.

- Family history of DDH (parents or siblings)

- Oligohydramnios (low levels of amniotic fluid)

Symptoms

Some babies born with a dislocated hip will show no outward signs.

Contact your pediatrician if your baby has:

- Legs of different lengths

- Uneven skin folds on the thigh

- Less mobility or flexibility on one side

- Limping, toe walking, or a waddling gait

Doctor Examination

In addition to visual clues, your doctor will perform a careful physical examination to check for DDH, such as listening and feeling for “clunks” as the hip is put in different positions. Your doctor will use specific maneuvers to determine if the hip can be dislocated and/or put back into proper position.

Newborns identified as at higher risk for DDH are often tested using ultrasound, which can create images of the hip bones. For older infants and children, x-rays of the hip may be taken to provide detailed pictures of the hip joint.

Treatment

When DDH is detected at birth, it can usually be corrected with the use of a harness or brace. If the hip is not dislocated at birth, the condition may not be noticed until the child begins walking. At this time, treatment is more complicated, with less predictable results.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment methods depend on a child’s age.

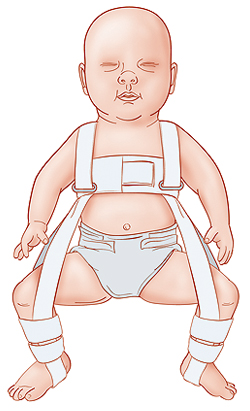

Newborns. The baby is placed in a soft positioning device, called a Pavlik harness, for 1 to 2 months to keep the thighbone in the socket. This special brace is designed to hold the hip in the proper position while allowing free movement of the legs and easy diaper care. The Pavlik harness helps tighten the ligaments around the hip joint and promotes normal hip socket formation.

Parents play an essential role in ensuring the harness is effective. Your doctor and healthcare team will teach you how to safely perform daily care tasks, such as diapering, bathing, feeding, and dressing.

1 month to 6 months. Similar to newborn treatment, a baby’s thighbone is repositioned in the socket using a harness or similar device. This method is usually successful, even with hips that are initially dislocated.

How long the baby will require the harness varies. It is usually worn full-time for at least 6 weeks, and then part-time for an additional 6 weeks.

If the hip will not stay in position using a harness, your doctor may try an abduction brace made of firmer material that will keep your baby’s legs in position.

In some cases, a closed reduction procedure is required. Your doctor will gently move your baby’s thighbone into proper position, and then apply a body cast (spica cast) to hold the bones in place. This procedure is done while the baby is under anesthesia.

Caring for a baby in a spica cast requires specific instruction. Your doctor and healthcare team will teach you how to perform daily activities, maintain the cast, and identify any problems.

6 months to 2 years. Older babies are also treated with closed reduction and spica casting. In most cases, skin traction may be used for a few weeks prior to repositioning the thighbone. Skin traction prepares the soft tissues around the hip for the change in bone positioning. It may be done at home or in the hospital.

Surgical Treatment

6 months to 2 years. If a closed reduction procedure is not successful in putting the thighbone is proper position, open surgery is necessary. In this procedure, an incision is made at the baby’s hip that allows the surgeon to clearly see the bones and soft tissues.

In some cases, the thighbone will be shortened in order to properly fit the bone into the socket. X-rays are taken during the operation to confirm that the bones are in position. Afterwards, the child is placed in a spica cast to maintain the proper hip position.

Older than 2 years. In some children, the looseness worsens as the child grows and becomes more active. Open surgery is typically necessary to realign the hip. A spica cast is usually applied to maintain the hip in the socket.

Recovery

In many children with DDH, a body cast and/or brace is required to keep the hip bone in the joint during healing. The cast may be needed for 2 to 3 months. Your doctor may change the cast during this time period.

X-rays and other regular follow-up monitoring are needed after DDH treatment until the child’s growth is complete.

Complications

Children treated with spica casting may have a delay in walking. However, when the cast is removed, walking development proceeds normally.

The Pavlik harness and other positioning devices may cause skin irritation around the straps, and a difference in leg length may remain. Growth disturbances of the upper thighbone are rare, but may occur due to a disturbance in the blood supply to the growth area in the thighbone.

Even after proper treatment, a shallow hip socket may still persist, and surgery may be necessary in early childhood to restore the normal anatomy of the hip joint.

Outcomes

If diagnosed early and treated successfully, children are able to develop a normal hip joint and should have no limitation in function. Left untreated, DDH can lead to pain and osteoarthritis by early adulthood. It may produce a difference in leg length or decreased agility.

Even with appropriate treatment, hip deformity and osteoarthritis may develop later in life. This is especially true when treatment begins after the age of 2 years.

There are no reviews yet.