Kyphosis

In the majority of cases, kyphosis causes few problems and does not require treatment. Occasionally, a patient may need to wear a back brace or do exercises in order to improve his or her posture and strengthen the spine. In severe cases, however, kyphosis can be painful, cause significant spinal deformity, and lead to breathing problems. Patients with severe kyphosis may need surgery to help reduce the excessive spinal curve and improve their symptoms.

Kyphosis (Roundback) of the Spine

Anatomy

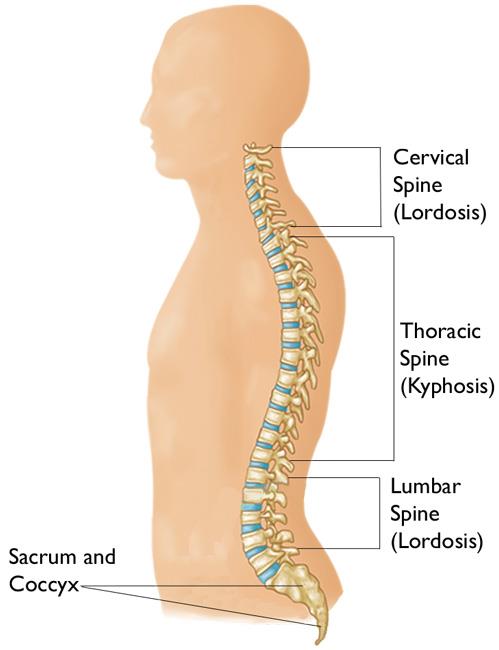

Your spine is made up of three segments. When viewed from the side, these segments form three natural curves.

The “c-shaped” curves of the neck (cervical spine) and lower back (lumbar spine) are called lordosis. The “reverse c-shaped” curve of the chest (thoracic spine) is called kyphosis.

This natural curvature of the spine is important for balance and helps us to stand upright. If any one of the curves becomes too large or too small, it becomes difficult to stand up straight and our posture appears abnormal.

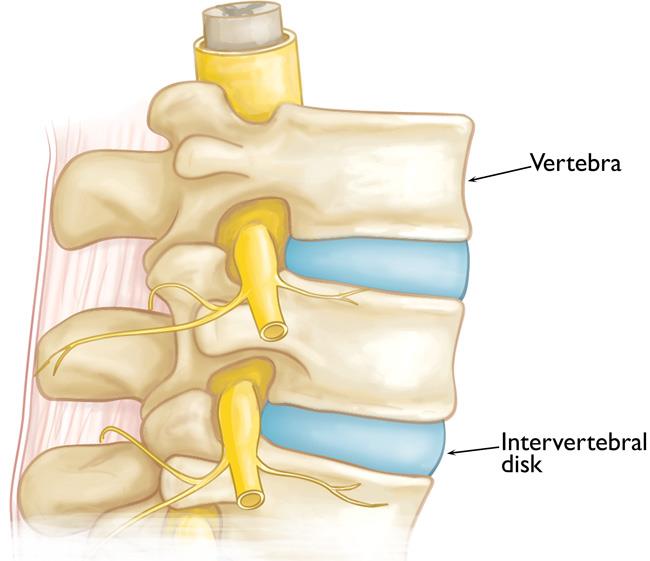

Other parts of your spine include:

Vertebrae. The spine is made up of 24 small rectangular-shaped bones, called vertebrae, which are stacked on top of one another. These bones create the natural curves of your back and connect to create a canal that protects the spinal cord.

Intervertebral disks. In between the vertebrae are flexible intervertebral disks. These disks are flat and round and about a half inch thick. Intervertebral disks cushion the vertebrae and act as shock absorbers when you walk or run.

Description

Although the thoracic spine should have a natural kyphosis between 20 to 45 degrees, postural or structural abnormalities can result in a curve that is outside this normal range. While the medical term for a curve that is greater than normal (more than 50 degrees) is actually “hyperkyphosis,” the term “kyphosis” is commonly used by doctors to refer to the clinical condition of excessive curvature in the thoracic spine that leads to a rounded upper back.

Kyphosis can affect patients of all ages. The condition, however, is common during adolescence—a time of rapid bone growth.

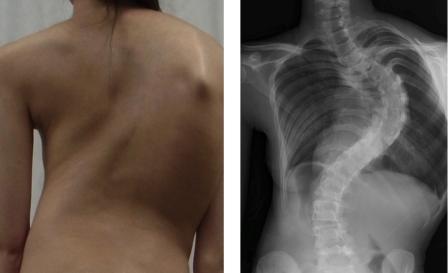

Kyphosis can vary in severity. In general, the greater the curve, the more serious the condition. Milder curves may cause mild back pain or no symptoms at all. More severe curves can cause significant spinal deformity and result in a visible hump on the patient’s back.

Types of Kyphosis

There are several types of kyphosis. The three that most commonly affect children and adolescents are:

- Postural kyphosis

- Scheuermann’s kyphosis

- Congenital kyphosis

Postural Kyphosis

Postural kyphosis, the most common type of kyphosis, usually becomes noticeable during adolescence. It is noticed clinically as poor posture or slouching, but is not associated with severe structural abnormalities of the spine.

The curve caused by postural kyphosis is typically round and smooth and can often be corrected by the patient when he or she is asked to “stand up straight.”

Postural kyphosis is more common in girls than boys. It is rarely painful and, because the curve does not progress, it does not usually lead to problems in adult life.

Scheuermann’s Kyphosis

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is named after the Danish radiologist who first described the condition.

Like postural kyphosis, Scheuermann’s kyphosis often becomes apparent during the teen years. However, Scheuermann’s kyphosis can result in a significantly more severe deformity than postural kyphosis—particularly in thin patients.

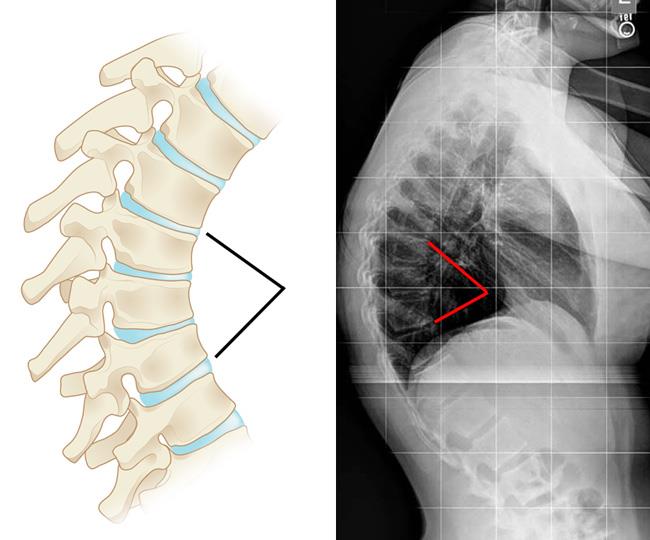

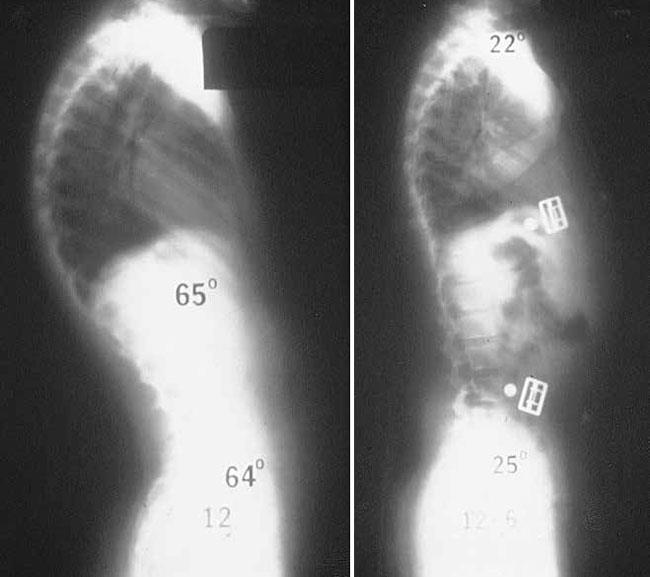

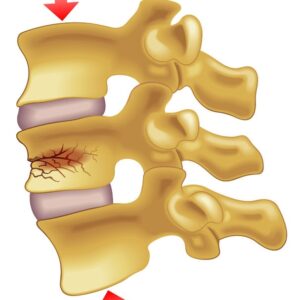

Scheuermann’s kyphosis is caused by a structural abnormality in the spine. In a patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis, an x-ray from the side will show that, rather than the normal rectangular shape, several consecutive vertebrae have a more triangular shape. This irregular shape causes the vertebrae to wedge together toward the front of the spine, decreasing the normal disk space and creating an exaggerated forward curvature in the upper back.

The curve caused by Scheuermann’s kyphosis is usually sharp and angular. It is also stiff and rigid; unlike a patient with postural kyphosis, a patient with Scheuermann’s kyphosis is not able to correct the curve by standing up straight.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis usually affects the thoracic spine, but occasionally develops in the lumbar (lower) spine. The condition is more common in boys than girls and stops progressing once growing is complete.

Scheuermann’s kyphosis can sometimes be painful. If pain is present, it is commonly felt at the highest part or “apex” of the curve. Pain may also be felt in the lower back. This results when the spine tries to compensate for the rounded upper back by increasing the natural inward curve of the lower back. Activity can make the pain worse, as can long periods of standing or sitting.

Congenital Kyphosis

Congenital kyphosis is present at birth. It occurs when the spinal column fails to develop normally while the baby is in utero. The bones may not form as they should or several vertebrae may be fused together. Congenital kyphosis typically worsens as the child ages.

Patients with congenital kyphosis often need surgical treatment at a very young age to stop progression of the curve. Many times, these patients will have additional birth defects that impact other parts of the body such as the heart and kidneys.

Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of kyphosis vary, depending upon the cause and severity of the curve. These may include:

- Rounded shoulders

- A visible hump on the back

- Mild back pain

- Fatigue

- Spine stiffness

- Tight hamstrings (the muscles in the back of the thigh)

Rarely, over time, progressive curves may lead to:

- Weakness, numbness, or tingling in the legs

- Loss of sensation

- Shortness of breath or other breathing difficulties

Doctor Examination

Mild kyphosis often goes unnoticed until a scoliosis screening at school—and this prompts a visit to the doctor. If changes to the patient’s back are noticeable, however, it is usually quite troubling for both the parents and the child. Concern about the cosmetic appearance of the child’s back is often what leads the family to seek medical help.

Physical Examination

Your doctor will begin by taking a medical history and asking about your child’s general health and symptoms. He or she will then examine your child’s back, pressing on the spine to determine if there are any areas of tenderness.

In more severe cases of kyphosis, the rounding of the upper back or a hump may be clearly visible. In milder cases, however, the condition may be harder to diagnose.

During the exam, your doctor will ask your child to bend forward with both feet together, knees straight, and arms hanging free. This test, which is called the “Adam’s forward bend test,” enables your doctor to better see the slope of the spine and observe any spinal deformity.

Your doctor may also ask your child to lay down to see if this straightens the curve—a sign that the curve is flexible and may be representative of postural kyphosis.

Tests

X-rays. These studies provide images of dense structures, such as bone. Your doctor may order x-rays from different angles to determine if there are changes in the vertebrae or any other bony abnormalities.

X-rays will also help measure the degree of the kyphotic curve. A curve that is greater than 50 degrees is considered abnormal.

Pulmonary function tests. If the curve is severe, your doctor may order pulmonary function tests. These tests will help determine if your child’s breathing is restricted because of diminished chest space.

Other tests. In patients with congenital kyphosis, progressive curves may lead to symptoms of spinal cord compression, including pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness in the lower body. If your child is experiencing any of these symptoms, your doctor may order neurologic tests or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to stop progression of the curve and prevent deformity. Your doctor will consider several things when determining treatment for kyphosis, including:

- Your child’s age and overall health

- The number of remaining growing years

- The type of kyphosis

- The severity of the curve

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment is recommended for patients with postural kyphosis. It is also recommended for patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who have curves of less than 75 degrees.

Nonsurgical treatment may include:

Observation. Your doctor may recommend simply monitoring the curve to make sure it does not get worse. Your child may be asked to return for periodic visits and x-rays until he or she is fully grown.

Unless the curve gets worse or becomes painful, no other treatment may be needed.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can help relieve back pain and improve posture by strengthening muscles in the abdomen and back. Certain exercises can also help stretch tight hamstrings and strengthen areas of the body that may be impacted by misalignment of the spine.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs, including aspirin, ibuprofen and naproxen, can help relieve back pain.

Bracing. Bracing may be recommended for patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who are still growing. The specific type of brace and the number of hours per day it should be worn will depend upon the severity of the curve. Your doctor will adjust the brace regularly as the curve improves. Typically, the brace is worn until the child reaches skeletal maturity and growing is complete.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is often recommended for patients with congenital kyphosis.

Surgery may also be recommended for:

- Patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis who have curves greater than 75 degrees

- Patients with severe back pain that does not improve with nonsurgical treatment

Spinal fusion is the surgical procedure most commonly used to treat kyphosis.

The goals of spinal fusion are to:

- Reduce the degree of the curve

- Prevent any further progression

- Maintain the improvement over time

- Alleviate significant back pain, if it is present

Surgical Procedure

Spinal fusion is essentially a “welding” process. The basic idea is to fuse together the affected vertebrae so that they heal into a single, solid bone. Fusing the vertebrae will reduce the degree of the curve and, because it eliminates motion between the affected vertebrae, may also help alleviate back pain.

During the procedure, the vertebrae that make up the curve are first realigned to reduce the rounding of the spine. Small pieces of bone—called bone graft—are then placed into the spaces between the vertebrae to be fused. Over time, the bones grow together—similar to how a broken bone heals.

Before the bone graft is placed, your doctor will typically use metal screws, plates and rods to increase the rate of fusion and further stabilize the spine.

Exactly how much of the spine is fused depends upon the size of your child’s curve. Only the curved vertebrae are fused together. The other bones in the spine can still move and assist with bending, straightening, and rotation.

Long-Term Outcomes

If kyphosis is diagnosed early, the majority of patients can be treated successfully without surgery and go on to lead active, healthy lives. If left untreated, however, curve progression could potentially lead to problems during adulthood. For patients with kyphosis, regular check-ups are necessary to monitor the condition and check progression of the curve.

There are no reviews yet.